Why literacy is key for sustainable development

Today the world marks the International Literacy Day under the theme, “Transforming Literacy Learning Spaces”. According to UNESCO, this gives an opportunity to rethink the fundamental importance of literacy learning spaces to build resilience and ensure quality, equitable, and inclusive education for all. This day was first celebrated in 1967. Since then, annual celebrations have taken place around the world to champion the cause of literacy in building a more literate and sustainable society.

Humanity has enjoyed great progress over the past half century. Since 1970, global poverty rates have fallen from nearly 60% to 10%, and average life expectancy worldwide has risen from 55 to 70, thanks to increased literacy levels and skills. The global literacy rate has increased from just 1 in 8 adults being able to read to over 5 in 6. Millions of people have attained the required literacy skills that have enriched their lives and empowered them to create opportunities for themselves and their families.

Younger generations are quickly becoming more literate. In low- and middle-income countries alone, 91% of 15-24-year-olds are literate, relative to 85% of adults worldwide. However, events of the last few years are threatening to reverse the achievements that have been realized. In the aftermath of the pandemic, millions of children from vulnerable communities are being locked out of formal education in developing nations.

For those attending formal education, the situation is not better either. The World Bank has reported in what it calls a learning poverty that nearly six-out-of-ten children globally are estimated to be affected by learning poverty, meaning they are unable to read and understand a simple text by the age of ten. In low- and middle-income countries, the share is an estimated seven-out-of-ten children.

The World Bank says that children who cannot read and understand a simple text will struggle to learn anything else in school, and are more likely to repeat a grade and more likely to drop out of school. They are less likely to benefit from further training and skills programmes. At a national level, this will lead to worse health outcomes, greater youth unemployment and deeper levels of poverty.

We can continue doing business as usual – a decision that will intensify the learning poverty, and deepen socioeconomic inequities. Or we can begin a great reset that will lead us all toward a more sustainable, prosperous future where all children have an opportunity to quality learning that will dignify their lives.

We need bold actions from governments, stakeholders, and all players in the education sector to reset. Radical changes will be needed in the way we teach and deliver learning. We need to move quickly to seize high-impact opportunities — always informed by the best data and analysis available. We need to work with partners to meet the great scale of the challenge. Where leadership is needed, we will need to engage actively, building coalitions that will result to better literacy rates and learning outcomes.

A recent independent study by a Nobel prize winning economist found that the Bridge Schools teaching methodologies have the potential to produce dramatic learning gains. In the study, Professor Michael Kremer of the University of Chicago finds that the learning gains measured are big enough to boost a country’s national income by 5% every year within a generation if applied across the whole education system.

According to the groundbreaking study, underserved children receive 53% more learning over the course of their pre-primary and primary school career at Bridge International Academies in Kenya. It also found that grade 1 pupils, equivalent to P1 pupils, were more than three times as likely to be able to read as their peers in other schools.

Transforming literacy learning spaces

Literacy is measured in many ways around the world, often in self-reported and superficial ways. Real reading comprehension is almost never considered in national statistics measuring literacy. High literacy rates around the world mask the extent to which people can actually read with comprehension, the extent to which they are ‘functionally literate’, and can reap economic and social benefits from literacy.

The good news is that the gender literacy gap has been narrowing rapidly. In the past three decades, it has been halved – although adult men worldwide remain 8% more likely to be literate than women. In the study by Professor Michael Kremer, he finds that girls are receiving the same learning gains as boys. Traditionally, girls in Sub-Sahara Africa are consistently disadvantaged in learning against boys.

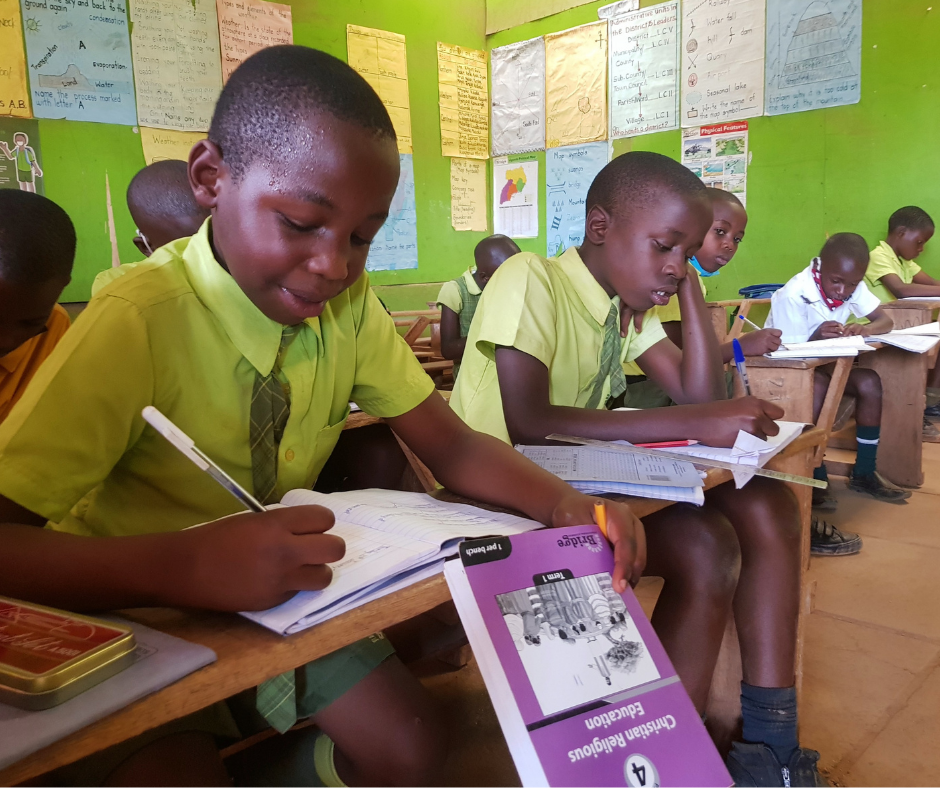

To achieve higher literacy skills, we need to transform our literacy learning spaces by empowering teachers and investing in tools and learning materials such as books that will boost learning outcomes.

In Uganda, children from rural and hard to reach areas are lagging behind in literacy and academic performance. Factors which mitigate against rural learners’ successful academic performance are untrained teachers, inadequate learning materials, poor infrastructure and poor school management practices. Books play an important role in advancing literacy. Unfortunately, the publishing industry in Uganda and many African countries face many challenges.

The book market is weak, resulting to inadequate reading materials hence a poor reading culture. Bridge Schools Uganda has published a series of PLE Revision Books which are designed to help prepare candidates to answer test questions. The books guide candidates through a revision programme that gives them a sense of confidence which is a necessary step to sitting an exam well.

The importance of literacy cannot be overstated. Literacy empowers children to deepen their learning independently both inside and outside the classroom. Literate parents can more effectively support their children’s own learning process, and higher literacy levels at the national and individual level are correlated with stronger health, employment opportunities, and productivity around the world.

Literacy is an essential human right. A good quality and basic education equip pupils with literacy skills for life and further learning. Literate parents are more likely to keep their children healthy and send their children to school. Literate people are able to better access other education and employment opportunities; and collectively, literate societies are better geared to meet development challenges sustainably.